TheClimateChanger

Members-

Posts

4,325 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Blogs

Forums

American Weather

Media Demo

Store

Gallery

Everything posted by TheClimateChanger

-

-

Pittsburgh/Western PA Fall 2023 Discussion

TheClimateChanger replied to Ahoff's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

And yet we have these crazy yinzers on Reddit who think it’s some sort of achievement not to run the heat by October 1: https://reddit.com/r/pittsburgh/s/1ePk1TxQI5 -

Wake Me Up When September Ends..Obs/Diso

TheClimateChanger replied to 40/70 Benchmark's topic in New England

Purple sun over Atlantic Canada today from dense wildfire smoke aloft. -

September 2023 General Discussion

TheClimateChanger replied to hardypalmguy's topic in Lakes/Ohio Valley

Interesting pattern. Unless the Canadian wildfires are under control by then, dense smoke looks possible as well. -

Wake Me Up When September Ends..Obs/Diso

TheClimateChanger replied to 40/70 Benchmark's topic in New England

-

Occasional Thoughts on Climate Change

TheClimateChanger replied to donsutherland1's topic in Climate Change

-

-

Occasional Thoughts on Climate Change

TheClimateChanger replied to donsutherland1's topic in Climate Change

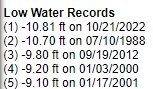

Saltwater intrusion a significant concern for the New Orleans area, as rising sea levels and severe drought are combining to enable the seawater to spread farther inland along the Mississippi. Of note, the gage level upstream at Memphis has fallen to -10.18 feet, and was as low as -10.29 feet earlier today (see graphic below). The forecast takes the level to -10.90 feet by October 10. This would exceed the low water record of -10.81 feet set last October. Previously, the lowest observed level was -10.70 feet, set in July 1988. -

Occasional Thoughts on Climate Change

TheClimateChanger replied to donsutherland1's topic in Climate Change

-

Faster than expected, that's been the theme for some time. I'm not surprised given the history of past climate changes on earth. The models are probably underestimating some of the synergistic feedbacks of climate warming.

-

September 2023 General Discussion

TheClimateChanger replied to hardypalmguy's topic in Lakes/Ohio Valley

-

Central PA Autumn 2023

TheClimateChanger replied to Itstrainingtime's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

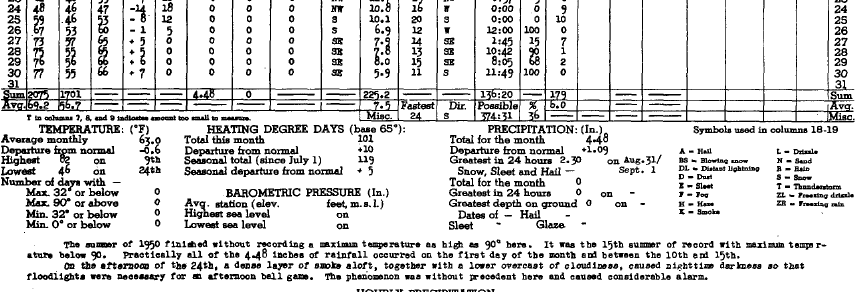

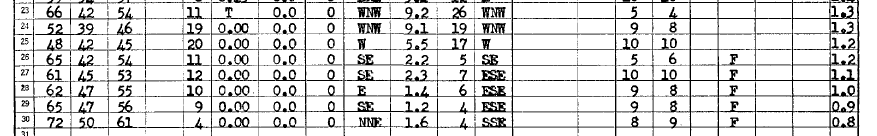

Here was the weather on September 24, 1950. Perhaps the most notable thing is the temperatures, which are almost unfathomable by today's standards for the month of September. Erie Erie had a high of 48F, and a low of 46F. The comment states: "On the afternoon of the 24th, a dense layer of smoke aloft, together with a lower overcast of cloudiness, caused nighttime darkness so that floodlights were necessary for an afternoon ball game. The phenomenon is without precedent here and caused considerable alarm." Williamsport Williamsport had a high of 52F and a low of 39F. Further down in the monthly summary, the Weather Bureau observer left the following remark: "The most outstanding phenomena of the month was the rather complete obscuration of all sunlight and skylight for a period of two hours late afternoon the 24th due to a thick, high level smoke stratum from western Canadian forest fires. General atmospheric smoke remained till the month's end in a stagnating air mass over the region." -

Central PA Autumn 2023

TheClimateChanger replied to Itstrainingtime's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

Also, of note, on yesterday's date 73 years ago, Black Sunday occurred in the Commonwealth. When I was looking up the history of wildfire smoke in the Commonwealth earlier in the summer with the seemingly near constant plumes of smoke, I came across this event from 1950. People were very perplexed, and many thought the world was ending or aliens were about to invade. Here are some reports from Bradford and Coudersport area. Bradford Landmark Society - The Day the Sun Went Out In Bradford - Bradford Pa History Historical Society Black Sunday: Darkness falls in the PA Wilds - Pennsylvania Wilds Some good eyewitness accounts on this site, with some even indicating stars were visible. This would suggest a large object eclipsed the sun outside of earth's atmosphere, perhaps giving some credence to the alien spacecraft theory. The official explanation today, however, is a pall of smoke from the Chinchaga firestorm in western Canada. darksunday (the-red-thread.net) -

Central PA Autumn 2023

TheClimateChanger replied to Itstrainingtime's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

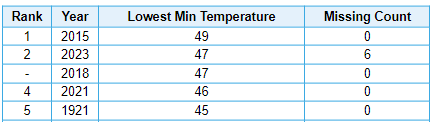

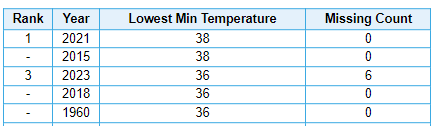

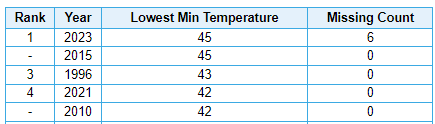

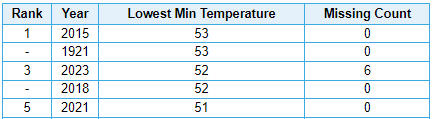

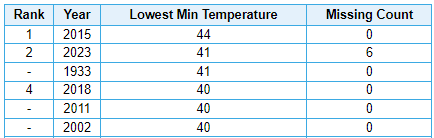

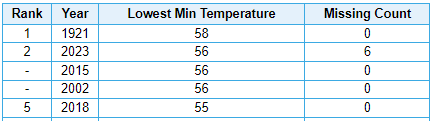

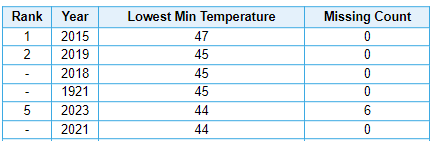

Interesting to see 1921 appear on several lists. That year seems like it was a little taste of the present climate in Pennsylvania, with hot summer months and high annual means as well. Wonder what happened to make it so warm that year. -

Central PA Autumn 2023

TheClimateChanger replied to Itstrainingtime's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

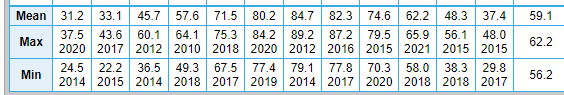

With 5 days left in the month, the coldest temperatures observed so far are among the absolute warmest on record for the month of September across much of the Commonwealth. Frosty weather has been missing in action, even across the highest of elevations. Williamsport Bradford DuBois Harrisburg/Middleton Mount Pocono Philadelphia Scranton -

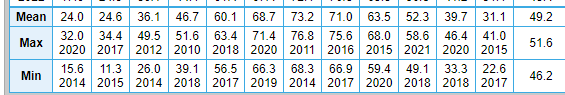

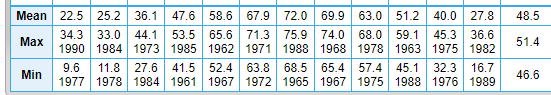

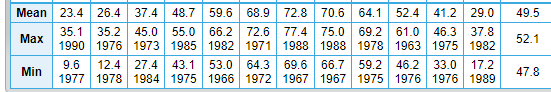

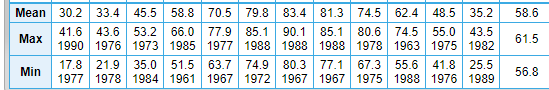

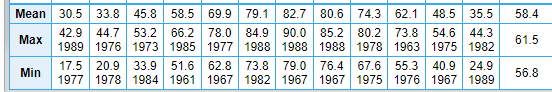

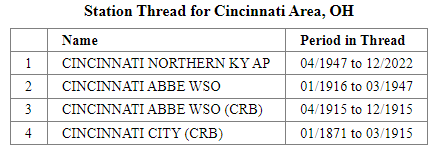

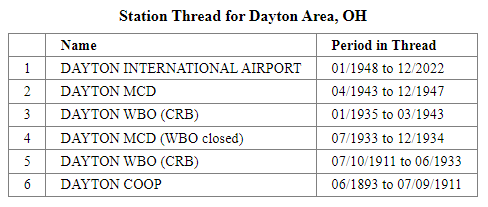

Also, it's not true that I cherrypicked the summer months. At Flint, the change in annual temperatures is just as great if not more. It is true that Detroit's annual mean has not "shifted" quite as much as the summer mean, but very close. Looking at the past 13 years, the annual mean at Detroit is within a couple tenths of a degree of the 1961-1990 average for Columbus and Dayton, Ohio. The values below compare 2010-2022 (13 years) at Flint to 1961-1990 averages at Toledo and Findlay, Ohio. I expect the Flint average to come up another tenth of a degree when 2023 is finished, but I've excluded 2023 since it's still in progress. First up is annual mean for Flint. The past 13 years have averaged 49.2F for the annual mean. At Toledo, the 1961-1990 average for annual mean was 48.5F. At Findlay, the 1961-1990 average for annual mean was 49.5F. The annual mean temperature at Flint over the past 13 years has been 0.7F warmer than the 1961-1990 normal at Toledo, Ohio and 0.3F cooler than the 1961-1990 normal at Findlay, Ohio. And I can already anticipate the next objection. Oh - but it's mostly being driven by warmer low temperatures. Wrong! The annual mean maximum temperature has shifted even more than the annual mean average temperature. The mean average annual maximum temperature at Flint, Michigan over the past 13 years has been an astounding 59.1F. This is 0.5F warmer than the mean at Toledo for 1961-1990. And 0.7F warmer than the mean at Findlay for 1961-1990.

-

September 2023 General Discussion

TheClimateChanger replied to hardypalmguy's topic in Lakes/Ohio Valley

@hardypalmguy -

Pittsburgh/Western PA Fall 2023 Discussion

TheClimateChanger replied to Ahoff's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

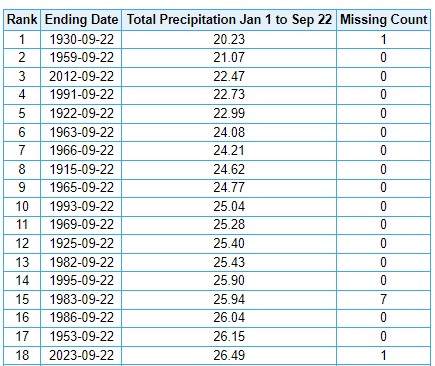

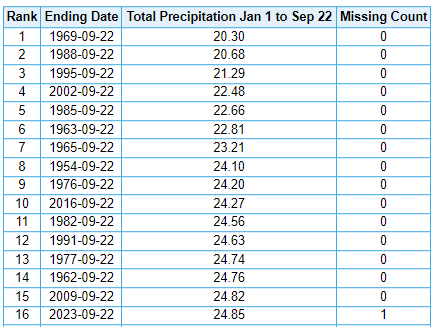

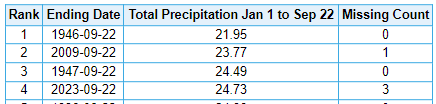

Similar situation in northern West Virginia. I used a cutoff of 25 missing days to avoid bad data - of course, even a handfull of missing days could potentially affect these numbers. Using the above cutoff, MGW is in 18th place (out of 122 years). Wheeling is in 13th place, out of 67 years - although several years could have received more rainfall than shown due to missing data. Interestingly, Wheeling has received quite a few more recent dry years since the installation of the ASOS at the county airport than other sites. I wouldn't have expected it to be drier there, given its elevation several hundred feet above the river. Allowing for up to 50 missing days, HLG is in 15th place of 80 years. It might be surprising that a lot of the additional years had more rainfall, but often the missing data is simply the observer not indicating 0 precipitation fell. Of course, anytime 28 or more days are missing, there could be an entire month's worth of data missing. -

Pittsburgh/Western PA Fall 2023 Discussion

TheClimateChanger replied to Ahoff's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

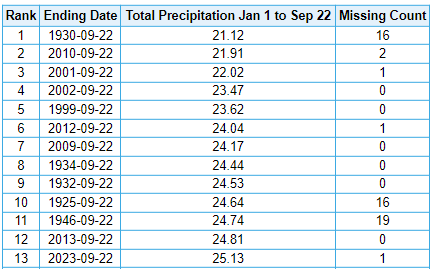

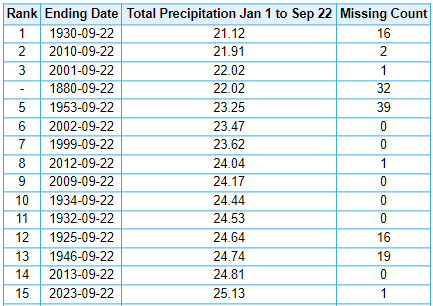

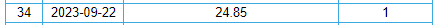

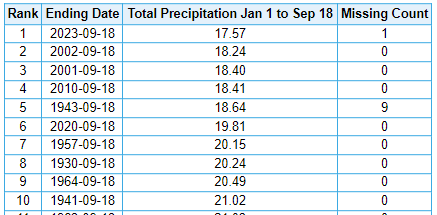

A little bit of D0 noted in parts of western Pennsylvania in the most recent drought monitor update. Somewhat surprised southwest Pennsylvania has escaped the D0 so far. In the threaded record, this year has been the 34th driest to date (out of 153 years). Limiting the comparison to Pittsburgh International Airport records, as the downtown site tended to be a bit drier, it's the 16th driest (out of 72 years). As you can see, only three years this century have been drier to date (2002, 2016, and 2009), and one of those three (2009) is essentially in a tie with this year with just 0.03" less. At Allegheny County Airport, it's been the 4th driest, out of 41 complete years of records (1936-1952, 2000-present). -

Pittsburgh/Western PA Fall 2023 Discussion

TheClimateChanger replied to Ahoff's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

-

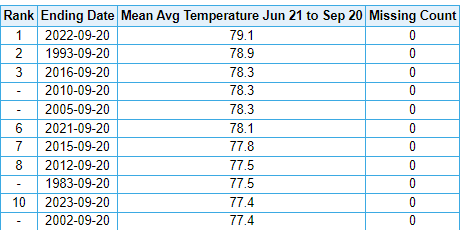

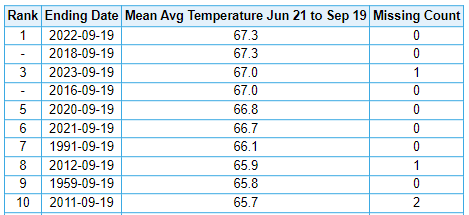

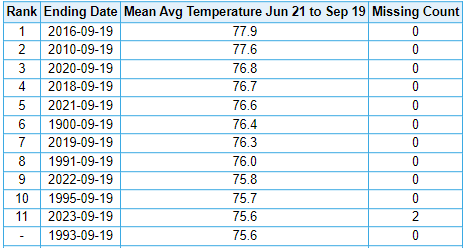

With two full days of astronomical summer left, Newark is sitting in 10th place for astronomical summer. One caveat, realize the dates can vary by about a day in either direction, but this analysis uses the period June 21 to date for ease of comparison. Prior to 2005, only two warmer astronomical summers are noted (1993 & 1983). While it's in 10th place out of 124 years of data, it is only in third place out of the past three years and seventh place of the past 14 years. So very warm historically - as I noted, it would have been 3rd warmest prior to 2005 - but only about on par for the past decade and a half. And possibly with it being only the 3rd warmest since 2021, it may be a cool astronomical summer in the current climate.

-

The only reason the 1931-1960 average is that much higher than the 1961-1990 average in the threaded records is because the first half of that data were from the city offices. Unlike Detroit, the airports are 300 to 500 feet higher in elevation than the cities - not to mention the decreased urban heat island effect from moving away from a rooftop in the central business district to a suburban location. It might have been a bit warmer, but not by 1.5F. My original analysis used 1961-1990 average for a few reasons - none of which involved picking cherries: (1) Most importantly, this was the date period referenced in the original claim; (2) It represents what was considered to be the "normal climate" a lot of us experienced when we began following the weather in the 1990s and start of the 2000s; and (3) It avoids the problem of mixing in data from various locations, altitudes and exposures (see note above) - all of the records compared were from the same locations and with more modern and reliable equipment characteristic of the late 20th century.

-

Central PA Autumn 2023

TheClimateChanger replied to Itstrainingtime's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

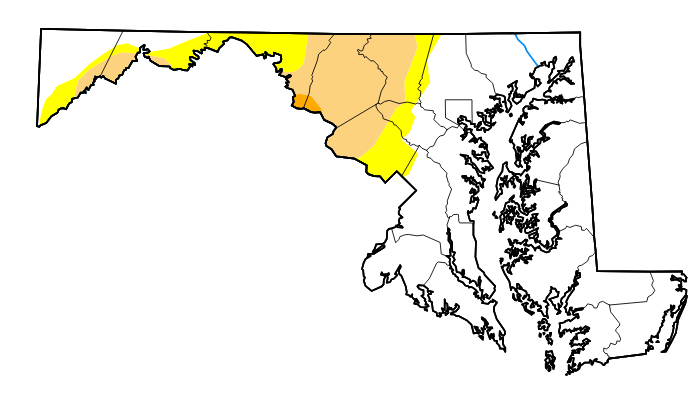

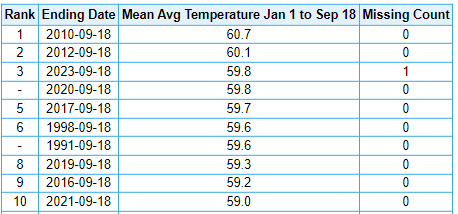

Yeah, this is a notable combination for Hagerstown: 3rd warmest and driest YTD. Surprisingly, very little drought with most of Washington County labelled only as abnormally dry (see below). Regarding temperatures on a year-to-date basis, 8 out of the top 10 warmest have occurred since within the past 14 years, and expanding out a bit (not shown) 9 of the top 12 and 10 of the top 14. Curiously, 3 of the top 6 driest YTD periods have also occurred in the past 14 years, with 5 of the top 6 from the 21st century. 3rd warmest year to date Driest year to date Maryland Drought Monitor -

Central PA Autumn 2023

TheClimateChanger replied to Itstrainingtime's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

Heck of a way to run a cool summer! -

Central PA Autumn 2023

TheClimateChanger replied to Itstrainingtime's topic in Upstate New York/Pennsylvania

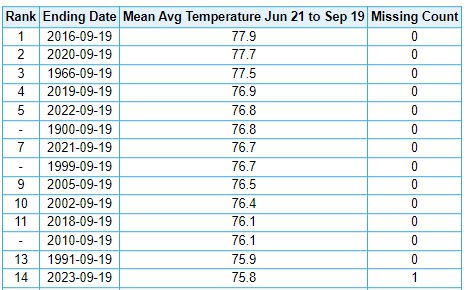

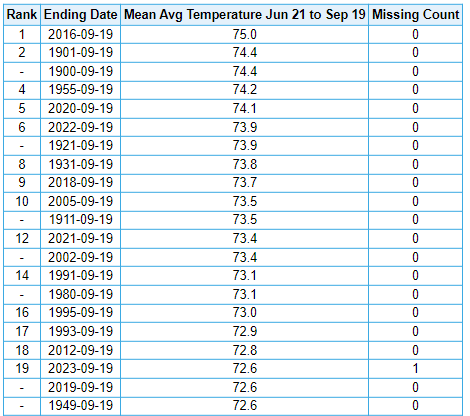

HOT DIGGITY DOG! With the fall equinox looming in a few days, I figured I'd take a look at the numbers for astronomical summer. Although, admittedly, the date of the summer solstice can vary slightly from the 6-21 start I used. This has been the 3rd warmest astronomical summer to date in Bradford, Pennsylvania (out of 65 years): This is the 14th warmest at Harrisburg (out of 136 years): This is the 19th warmest at Williamsport (out of 129 years): Just across the Mason-Dixon line, this has been the 11th warmest astronomical summer at Hagerstown, Maryland: